From Perfume to Hand Sanitiser, LVMH’s Act of Philanthropy not Seen Since World War II

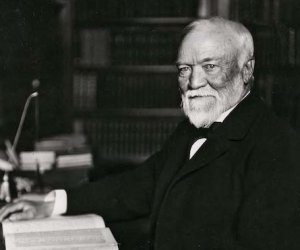

LVMH has ordered its parfums facilities to produce hand sanitisers in order to combat the coronavirus, a move which has not been seen since WW2 when watchmakers made arms. Who was the influence? Pioneering Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

- Andrew Carnegie

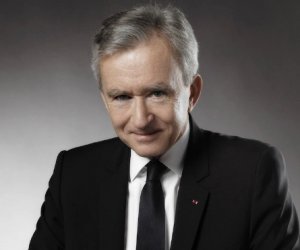

- Bernard Arnault

In every continent, today’s philanthropists acknowledge the enduring influence of Andrew Carnegie. But on Sunday 15th March 2020, LVMH Moët Hennessy took Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth philosophy to the next level. The Louis Vuitton owner ordered that its perfume and cosmetics facilities be re-tooled to manufacture hydroalcoholic gel or hand sanitiser.

Lauren Sherman, Executive Editor of Business of Fashion reported that the directive came straight from LVMH chairman and chief executive Bernard Arnault, though it was not confirmed, yesterday, Monday the 16th saw facilities that produce fragrances and cosmetics for Christian Dior, Guerlain, and Givenchy switching over to hand sanitisers and hand disinfectant gel, which will be given to French health authorities and hospitals free of charge.

“LVMH will use the production lines of its perfume and cosmetic brands…to produce large quantities of hydroalcoholic gels from Monday. These gels will be delivered free of charge to the health authorities. LVMH will continue to honour this commitment for as long as necessary, in connection with the French health authorities.” LVMH statement

From Perfume to Hand Sanitiser, LVMH’s Act of Philanthropy not Seen Since World War II

During World War II, America’s manufacturing might was key to the Allied victory. By the beginning of 1944, the output of American factories was twice that of all the Axis nations as manufacturers, including watchmakers like Hamilton, Bulova and Waltham, shut down normal operations and retooled for wartime; in essence, LVMH’s act of philanthropy in switching from cosmetics to hand sanitiser has not been seen in over 70 years and their’s is an act (especially if this influences other industries to join them – creating medical diagnostic tools, masks and other vital medical supplies) that would appear to be the key in our own allied victory against the coronavirus.

American watchmakers like Hamilton, Waltham-Longines and Bulova re-tooled their factories to produce weapons and ammunition for the US army during World War II

Gospel of Wealth – A classic model for modern corporate social responsibility

Having made his fortune in Pittsburgh America, Carnegie is indisputably the world’s greatest ever philanthropist. If you’ve heard of the Carnegie name, it’s likely you’ve discovered it from the many libraries, universities and scholarships awarded to the poor and disenfranchised. In addition to feeding the mind, Carnegie believed in feeding the soul, creating spaces for appreciating music and culture, like the famed namesake Carnegie Hall in New York. By the time he died in 1919, Carnegie had already given away more than 90% of his fortune $350 billion (adjusted for 2020 inflation) wealth accumulated as the world’s biggest steel maker. No one comes near to him for the scale of giving much more than today’s biggest donors Bill and Melinda Gates.

What makes him so influential is how most of our modern conglomerates and conglomerate owners behave today mirrors his ideals: Carnegie wasn’t the just the world’s biggest philanthropist, he was the world’s most modern philanthropist. His treatise, the Gospel of Wealth has set down the principles for giving that many of today’s ultra-wealthy are measured against when it comes to giving back to society.

Carnegie sponsored the construction of the Peace Palace in the Hague originally built to provide a home for the Permanent Court of Arbitration, a court created to end war by the Hague Convention of 1899

If the portrait of a billionaire philanthropist seems familiar today, it is directly as a result of Andrew Carnegie’s pioneering giving; in his day, it was revolutionary. In case you have not yet noticed, most philanthropic efforts today, either from on an individual or corporate scale, is modelled on Carnegie’s ideals chronicled in his Gospel of Wealth: financial donations are put to nourishing society’s most disadvantaged in a holistic manner – mind, body and soul.

Carnegie’s philanthropic vision was extraordinarily futurist: he gave millions to promote peace and disarmament but his greatest idea was one where he thought that if all the great industrialists (the high net worth individualists of his time) of the world came together, World Wars could be prevented. Indeed, given the globalised nature of our interconnected economies, an active war with multiple nations on the scale of World War II is not as likely today but nevertheless, we still deal with existential threats to global peace in the form of international trade and economic warfare and third party “actors” in the case of the Covid-19 coronavirus which has now turned into a global pandemic.

“I know you would, rather than instead of building this, I had distributed it to you in the form of higher wages. That’s what you think would have been proper? But if I had given you more money in your pay cheques, what would you have done with it? You might have bought a better cut of meat for the family. You might have spent it on drink. But I know what you need: You need a library. You need a museum, you need a concert hall. These is what raises the working man. And that’s why I saved this money. And I’m now giving back to the community what the community needs.” – Andrew Carnegie on the opening of his library in Pittsburgh

This photograph taken on June 26, 2018, shows the transcept of Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral in Paris. (Photo by Ludovic MARIN / AFP)

Dealing with the “contradictions” of modern philanthropy

When the Notre Dame de Paris caught fire back in April 2019, the outpouring of global grief and the pledging of vast sums of money towards its re-build and restoration prompted an equivalent push back of social justice warriors wondering if the money could have been better spent “feeding the poor” or “housing the homeless”. This “contradiction” as been a 200 year old problem which Carnegie himself dealt with during the peak of the 19th century. In his usual brusque manner, he told a crowd of employees during the opening of his namesake library in Pittsburgh, “I know you would, rather than instead of building this, I had distributed it to you in the form of higher wages. That’s what you think would have been proper? But if I had given you more money in your paycheques, what would you have done with it? You might have bought a better cut of meat for the family. You might have spent it on drink. But I know what you need: You need a library. You need a museum, you need a concert hall. These are what raises the working man. And that’s why I saved this money. And I’m now giving back to the community what the community needs.”

While his condescension might not have been well received, his vexatious annoyance with small-mindedness is really aimed towards a psychological issue in how most human beings process information. Case in point, Philippe Martinez, leader of the General Confederation of Labor trade union once stated, “If they can give tens of millions to rebuild Notre Dame, then they should stop telling us there is no money to help with the social emergency.”

Notre Dame de Paris had oak interiors and pillars

It might be tempting to think you have to align yourself on the side of social justice warriors or billionaire foundations but philanthropic conundrums of this nature are a false dichotomy. Intellectually and philosophically speaking, there’s nothing wrong with donating to the restoration of a burned cathedral or contributing to the arts because humanity is not the sum of its basic needs and biological impulses. We need food for the body, just as we need sustenance for the mind and soul. We have urgent problems like homelessness, unequal food distribution and wealth inequality but we also have pressing concerns that deal with “preserving cultural identity” and our artistic heritage – philanthropy simply isn’t a zero-sum in the way we think.

The Gospel according to Andrew (Carnegie)

Even if not outright influenced by Carnegie’s Gospel of Wealth, many today mimic his pattern of giving and thinking. That said, Carnegie’s philanthropy eventually drove him to ever greater ruthlessness as a businessman. In his pursuit for “returning to society”, the former friend of the unions began dismantling the very institutions he had supported on the side of the working class he championed. Why? So his steel company could be more competitive and that he could make more money to give away.

Though he came to the realisation in the latter part of his life, his efforts in undoing the damage he had done were not sufficient and he took it upon himself to address what he saw as the fundamental challenges facing society in his time, a problem which very much exists till this day: the proper administration of wealth.

In the modern age where wealth is increasingly concentrated in the hands of the few, Carnegie’s gospel is just as relevant today as it was close to 200 years ago: In 1889, men like J. P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt and William Randolph Hearst, also known as “robber barons” were generating enormous fortunes and Carnegie had written his gospel to justify this concentration of wealth and to show how it could then be redistributed.

A Rolex Testimonee since 1994, David Doubilet is a pioneer and one of the best-known underwater photographers in the world. After publishing his first article in National Geographic in 1971, he swiftly gained recognition as one of the magazine’s top photographers. David Doubilet’s lens has captured all the waters of the planet.

He held that the first duty of the man of wealth, was to set an example of modest living, shunning display or extravagance, to provide moderately for the legitimate wants of those dependent upon him, and after doing so, to consider all surplus revenues which come to him simply as trust funds, for which he is called upon to administer and strictly bound as a matter of duty to administer in the manner which in his judgment is best calculated, to produce the most beneficial results to the community: Is it any wonder that the Hans Wilsdorf Foundation, established in 1945, which owns Rolex, donates a great deal of its income to charity and social causes in Geneva and around the world?

To Carnegie, wealth was a moral and ethical responsibility and his gospel did not make him a popular man: because nobody, least of all the rich and powerful, wants to be told that what they’re doing is immoral or lacking in ethical standing. Yet, in his perspective, men of wealth, economically the fittest of the modern civilisation do indeed have a duty to do the smart thing with the immense resources they can marshal towards the common good. Carnegie’s instruction to his contemporaries was truly radical and even today, relevant.

“He who dies rich, dies disgraced.” – Carnegie

LVMH and the marshalling of industrial resources

What LVMH has done with the production of hand sanitisers using their cosmetics facilities is exemplary. Especially so if its truly on the directive of French billionaire business magnate Bernard Jean Étienne Arnault. He was instrumental in establishing LVMH as a major patron of art in France when he established a cornerstone of the company in 1991 with corporate philanthropy initiatives that serve the general interest. More recently in 2019, Arnault pledged $200 million to the rebuilding of Notre Dame de Paris and $11 million to help fight the wildfires ravaging the Amazon rainforest; LVMH has also pledged $2.2 million to Chinese Red Cross in Wuhan to help with medical supplies but his latest move on marshalling industrial production resources from his facilities is inarguably wise on ethical, moral and economic grounds.

“(It) is not just about words and speeches or signing declarations of principle, it also requires taking concrete collective actions when dangers arise in order to provide resources for local specialists and work together to save our planet.” – Yann Arthus-Bertrand, LVMH Advisory Board Member

Retail is at a standstill, a growing number of cities are on lockdown, and rather than let factories (and employees) run fallow, LVMH has decided to put its massive capability and know-how at producing maximum public good – in this case, the literal disinfectant gel that will be delivered to French health authorities and the Assistance Publique-Hospitaux de Paris, a network of 39 teaching hospitals that treat more than eight million patients each year.

Meanwhile, France has closed eateries and other non-essential stores in an effort to combat the virus which has infected more than 156,000 people worldwide and killed at least 5,833. It is modern warfare the likes we have never seen. A truly globalised world and its interconnected economies mean that more than ever, the wealth and resources concentrated the hands of the few can be utilised to maximum effectiveness.

At press time: Chinese Billionaire Jack Ma has donated a total of 1.1 million testing kits, 6 million masks, and 60,000 protective suits and face shields in the African continent. His first shipment of 1 million masks and 500,000 coronavirus test kits arrived in the United States on Monday morning, yesterday.

After more than four decades of leading the most influential tech company in the world, Bill Gates has withdrawn from Microsoft to focus on philanthropic activities with special attention on “global health and development, education, and increasing engagement in tackling climate change.” The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was launched in 2000 and is reported to be the largest private foundation in the world, holding $46.8 billion in assets. Meanwhile, Amazon and Gates Foundation are in discussion to deliver coronavirus test kits to Seattle homes. Further proving that the needs of the world have evolved beyond mere financial aid but in the leveraging of production and logistics capability as demonstrated by the likes of LVMH. The Group projects that it will make 12 tons of hand sanitiser within its first week and it will continue to do so free of charge as long as France requires.