LVMH is betting big on Cha Ling, the French Made Traditional Chinese Medicine You’ve Never Heard Of

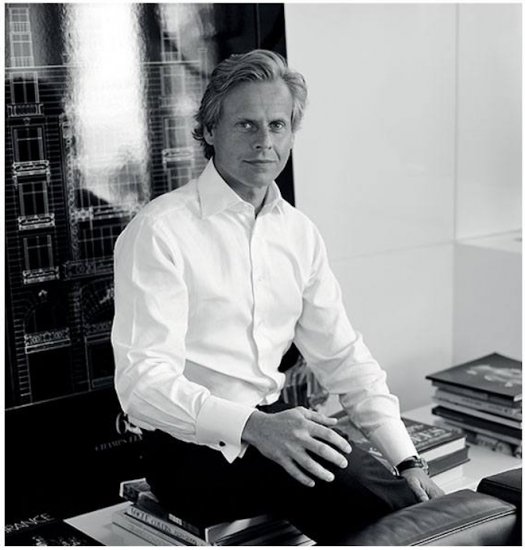

Laurent Boillot, CEO of Guerlain (LVMH Group) and founder of Cha Ling, the group’s first Traditional Chinese Medicine wellness brand is betting big on China.

If you have not heard of LVMH’s latest beauty and wellness brand Cha Ling, it’s not coincidental. It’s the French luxury conglomerate’s first foray into Traditional Chinese Medicine and a doubling down of the conglomerate’s investment on China, launched without fanfare save a single press release on LVMH Group’s corporate site in 2016.

During a private business meeting in June 2019, Citi Group analyst Thomas Chauvet noted that Louis Vuitton Chief Executive Michael Burke expressed that the brand was witnessing “un-heard of” growth rates in the Middle Kingdom on the backs of China’s efforts to reduce “daigou” – the practice of bringing in undeclared luxury goods from outside the country, usually with VAT claimed, for resale on the mainland. While this phenom is related to luxury handbags and accessories, the growing appetites of Chinese consumers is prompting LVMH to entrench themselves in more facets of Chinese lifestyle. Enter Cha Ling.

LVMH is betting big on Cha Ling, the French Made Traditional Chinese Medicine You’ve Never Heard Of

According to Ubifrance, foreign companies dominated the Chinese cosmetic market up until 2013, owning 60% of a 14-billion-euro market with French brands like L’Oréal Paris, Lancôme, Clarins, and Dior taking the lion’s share of the pie ahead from Japanese and US brands. By 2014, the tide had turned, according to Euromonitor, though sales of beauty products and make-up in China increased from 6.7% and 10.9% between 2014 and 2015 respectively, growing competition from Japanese, South Korean and home-grown Chinese brands had clawed back crucial market share from French dominance.

According to the China Shopper Report 2015, 2014 was also the first year where homegrown Chinese labels outperformed foreign brands, contributing to 87% of market growth representing almost 70% of market value in twenty-six product categories. Analysts were quick to point out that Chinese cosmetic brands didn’t get there on their sole marketing efforts alone, the Chinese government had made it a national policy to encourage citizens to “buy local” plus the confluence of growing numbers of Chinese looking to take care of their health and appearance.

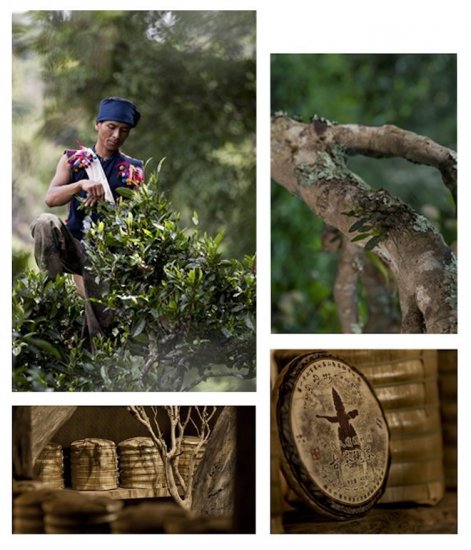

The world of beauty was introduced to Cha Ling, l’Esprit du Thé in 2016. A carefully articulated, well-executed bet where heritage French savoir-faire ventures deep into the Yunnan Province, specifically the Xishuangbanna region, in a region untouched by pollution and home to an ecosystem producing the world’s oldest variety of Pu’Er leaves.

When a pair of environmental champions, German biologist Josef Margraf and his Chinese wife Li Ming Guo met with Laurent Boillot, Chief Executive Officer of Guerlain, the idea of Cha Ling became the sort of “marriage in heaven”, one where a large luxury conglomerate could leverage their behemoth communications, retail and distribution engine to protect the “green lung” of China by not only promoting but also preserving the ecosystem of the region that produces Pu’Er tea.

Josef Magraf and wife, Li Ming Guo

The prestige segment of cosmetics is currently dominated by international brands like Procter & Gamble’s SK-II, even then SK-II, given its Japanese roots, has a largely Asian narrative of rice and authentic ingredients. Given this understanding, what Guerlain’s Chief really cottoned onto was the idea of a Sino-French cosmetics house which could neatly fall into the narrative of the government’s “buy local” policy while simultaneously being seen as a champion of sustainable development in China.

Guerlain CEO and Cha Ling founder, Laurent Boillot

Cha Ling might succeed where Shanghai Tang didn’t

After owning the brand since 2008 when luxury demand in China started to peak, Richemont finally divested its stake of Shanghai Tang in 2017. It was a business with potential but one fraught with the unchartered waters requiring astute cultural navigation. Eventually, a combination of off-the-rack cheongsam with out-of-touch pricing (since the cheongsam was traditionally a bespoke fitted garment) and the odd cultural crossroads where you were marketing a brand to a highly nationalistic citizenry where a large number of your clientele are gwai lo 鬼佬 or lao wai 老外 and you begin to have the ingredients for a contradiction of cultural expectations which eventually did them in. Yes, while Shanghai Tang represents an entirely different segment, the lessons are not dissimilar and it appears that Cha Ling largely avoids most of the hazards which typically accompanies what is essentially European adoption of authentically Chinese ingredients.

Cha Ling initially adopted the Euro-centric model of “origin” or provenance story as a core marketing tool which eventually pivoted to the SK-II model of focus on ingredients. Its championing of Pu’Er and with a third of its founding members being an ethnic Chinese woman no less, makes Cha Ling the kind of success story new undergrads will eventually read about in business school. It also helps that Guerlain CEO Boillot is passionate about Chinese culture, making it easy to avoid many of the tone-deaf marketing campaigns which has plagued some Euro-centric brands in China recently.

While international and domestic cosmetics brands alike are both subject to strict government regulation, the prevailing perception is that foreign brands are safer, use higher quality ingredients or simply more effective than their local partners. Hence, Chinese consumers are dawn to them despite higher prices.

For more than three years, Boillot mobilised the power of the LVMH Group to unlock the extraordinary cosmetic properties of Pu’Er leaves. Eventual scientific validation gave Boillot all the confirmation he needed to start Cha Ling. Never mind origin story, the ingredient, a widely recognised product but now specially harvested from an exotic locale, became the key selling point. One of the world’s oldest, most un-touched variety of Pu’Er tea: a powerful antioxidant also acting as an anti-pollutant and anti-ageing substance once matured.

Was it a calculated risk? You bet it was. According to Euromonitor, retail sales of skincare products in China reached 212.2 billion yuan ($30.85 billion) in 2018, representing year-on-year growth of 13.2 percent, with growth predicted to hit 32% by 2023. Cha Ling, a pro-China, French cosmetics label co-owned by a Chinese national with branding where the Chinese proper noun takes precedence? The gamble begins to look more like a sure investment.

Garnier withdrew from China in 2014.

All Cha Ling products are developed in Guerlain’s French lab but using exclusively Chinese ingredients. The Cha Ling line consists of 50 items from hand creams to fragrances, each retailing between €60 to €250. Sold in five Chinese boutiques in mainland metropolitan cities like Shanghai, as well as in Le Bon Marché.