Shape Your Time: Exploring Square and Form Watches of 2017

A cursory review of new 2017 watch collections have unveiled that while there is no resurgence of form watches, there’s never been a better time to get one.

Square watches, or in industry parlance: form or shaped watches are a fairly sizeable segment (given Cartier produces AND sells so many of them). That is to say, even though there’s a predominance of round watches in the industry, the belief that square or shaped watches are a niche segment is fundamentally untrue yet significant conversations with retailers and brands alike all indicate that the round watch, if anything, will dominate even more than it already does. For our part, we find this very disappointing indeed.

The much-reported preference of markets (apparently everywhere) for round watches seems like a self-fulfilling prophecy that no brand has seriously challenged. Well, one brand is challenging it but because that brand is Apple, watchmaking firms have only expressed tepid interest. More often than not, the companies have expressed aggressive disinterest.

This will mean that square watches will indeed be scarce, as we will illustrate here, and that fact represents an opportunity for the most consummate of collectors. The important thing is of course to see if there is enough demand to create the right sort of imbalance. Of course, we will be steering clear of making predictions as to investment value and such. Our purpose here is only to highlight an opportunity.

Designing Time

Before getting into that, let us look at the design situation at the turn of the last century, when the taste for wristwatches was still nascent. Louis Cartier was a jeweler with a penchant for what former Cartier CEO Franco Cologni called square surfaces. It was at the turn of the previous century that Cartier entered into its famous partnership with Parisian watchmaker Edmond Jaeger, who himself was tied up with the LeCoultre watchmaking company in Switzerland. This partnership prefigured the commercial launch of the Santos watch in 1911, a move that heralded the arrival of all sorts of new shapes in watchmaking.

The Panthere de Cartier is the major form watch release for 2017 that carries the codes of the Tank and the Santos.

At this time, before watchmakers and the public had any idea of what the ideal wristwatch would be, it was truly a free-for-all in terms of design. According to Cologni, in his book Cartier The Tank Watch, Louis Cartier was moved first and foremost by form, believing it to be more important than function. Arguably, this is the beginning of an idea that has an inherent weakness for the development and future of wristwatches– that function should follow form.

In contemporary times, the late Apple impresario Steve Jobs redefined this with his products, recognizing that “design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” As far as watchmaking goes, the idea that design is how the object itself functions speaks to why so many watches today are round. Our daily time is indeed circular because that is what happens when you track the hours and minutes with hands. This powerful idea then shapes a powerful commercial argument.

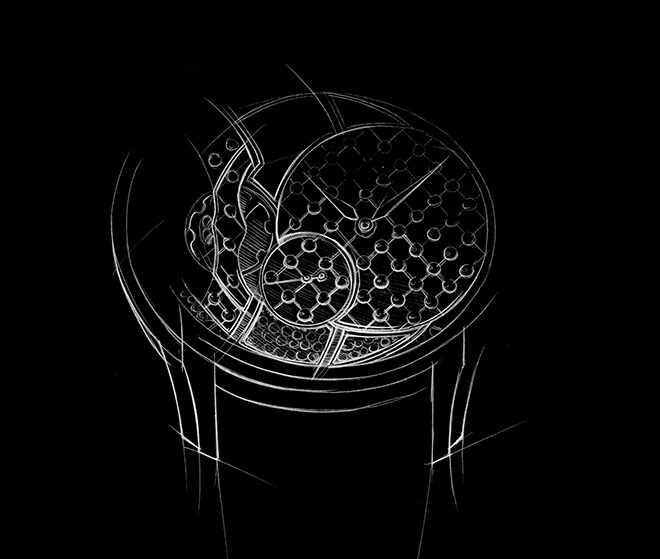

- Audemars Piguet is one of the few with a strong oval watch collection that also comes with a shaped movement

- The Audemars Piguet Millenary Quadriennium brought to life from the sketch before

Fragmented Collections

When asked about the new IWC Da Vinci being round despite the 2007 version being a refreshingly complex tonneau-tortue shape, here is what then-IWC CEO Georges Kern said: “The point is, 70 percent of the market is round watches. And the shaped segment is very limited and further segmented: square, rectangular, baignoire, tonneau… At the size IWC is today, with our reach, you need to be round because that’s what the market is.”

Kern was heading up watchmaking, marketing and digital for the Richemont Group overall so what he says carries weight far beyond IWC.

- By virtue of its contrast bezel, the Panerai Luminor Submersible 1950 PAM684 is a form watch hiding in round clothes.

- Despite predictions to the contrary, the Apple Watch Series 2 stuck with the rectangular shape and is water resistant to 50 metres.

- Franck Muller enjoyed a peak in the 90s and the early 2000s giving tonneau shaped watches a boost in popularity, pictured here, the Vanguard Fullback.

In fact, Kern’s estimation is generous considering that most informed sources consider round watches to be closer to 80 percent of the market. Before proceeding though, the market itself requires some definition because it does not only include the high-end market, meaning watches above US$1,000. In a 2015 article on the then-upcoming Apple Watch Series 2, no less than Forbes predicted that Apple would abandon its signature look in favour of the more conventional round shape. This prediction was based on the input of industry insiders and the like, and no doubt also took Jobs’ own philosophy into account. Of course, Apple confounded these expectations, illustrating again the hazards of journalists predicting outcomes. Considering that the Apple Watch 2 is both a status symbol and below US$1,000 (it is available for as little as $398 from the Apple Store), its very existence threatens the narrative that the market is overwhelmingly interested in round watches.

Exploring Form and Shaped Watches

Despite being, in the official lingo “timeless”, watches certainly mirror the era they are made and released in. This is what makes vintage watches from some periods – particularly the Art Deco age – so distinctive. Given the importance of heritage to the core of Swiss watchmaking – fine and otherwise – the brands have done a good job of retaining certain aesthetic touches across the ages. We have already gone into why Jaeger-LeCoultre shares the rectangular watch crown with Cartier. Both these firms maintain and champion in the 21st century a look that was already classic in the 1950s. But form watches – which are otherwise known as shaped watches – are not just rectangular of course.

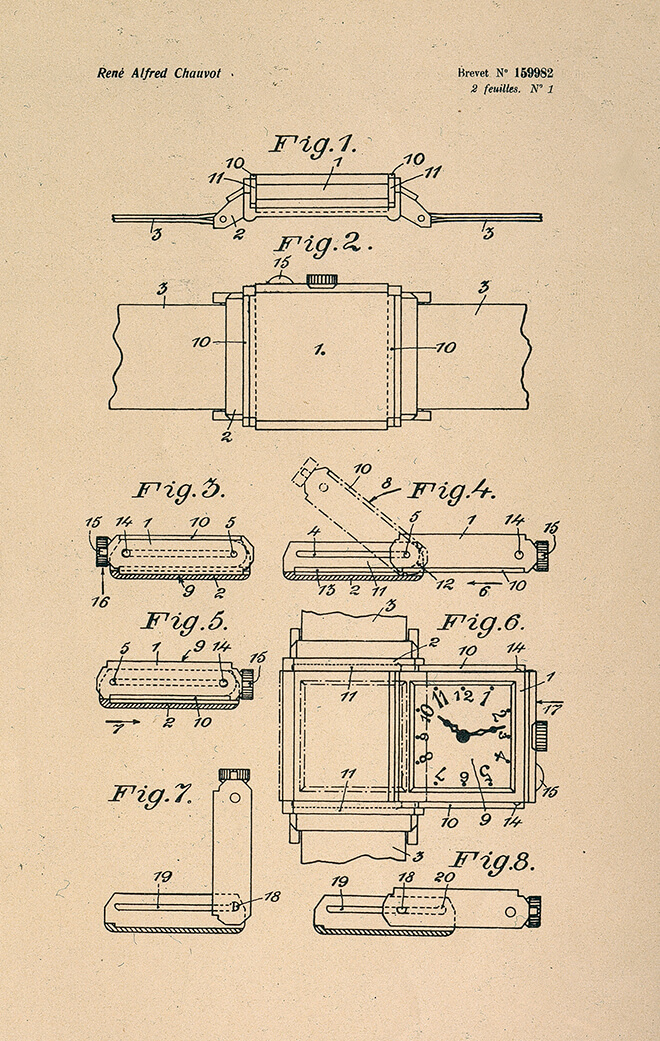

- Patent drawing of the original Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso

- The 2017 Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso Tribute Duo owns the form space in classical styling

In official parlance, any watch that isn’t round is called a “form watch.” So that means everything from cushion-shaped Panerai watches to every collection from Cartier other than the Drive de Cartier, Cle de Cartier and Calibre de Cartier; we would argue that the popular Ballon Bleu is actually a form watch because it has a tactile appeal arising from its pebble shape. To look at the number of models in the form watch segment itself, we can only reference other magazines. Armbanduhren, a specialty German watch catalog, lists more than 1,000 models of watches (and has done since we began paying attention, in 2011). Of these more than 900 are round, meaning that form watches are roughly 10 percent of the annual offering.

If we take these numbers to base an extrapolation on, then we have roughly 10 percent of the watch models in any given year vying for potentially 30 percent of the market. Of course, we have no way of knowing just how many pieces are made and sold directly but it seems a good bet that only Cartier will be selling form watches in significant numbers.

Drive de Cartier pushes the cushion-shaped aesthetic, here in extra flat form.

This brings us to sales, briefly. Forbes ranks Rolex as the top-selling brand of high-end Swiss watches and Omega as the third. Guess what brand occupies the second rung? Yes, the standard-bearer of form watches itself, the Panthere of fine watchmaking, Cartier sells the most watches annually, other than Rolex.

Square and Rectangle Watches

The Tank is probably the most famous form watch in the world, rivaled only by the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso. If one throws in the very popular and aforementioned Santos, also from Cartier, as well as the Twenty4, Nautilus and Aquanaut from Patek Philippe, and the Cintrex Curvex from Franck Muller, these are probably the most widely known form watches on the planet. Leaving all these aside and returning to just Cartier, this powerful brand has sought to increase its market share by unleashing an array of round watches but of these, the Ballon Bleu is so rounded that it resembles a sort of magical pebble that tells the time. The shape of this watch is, arguably, what made it an unqualified success. Nevertheless, Cartier clearly feels like its best shot at gaining market share lies with round watches, lending no small amount of credence to Kern’s statement.

- Patek Philippe Aquanaut 5168G

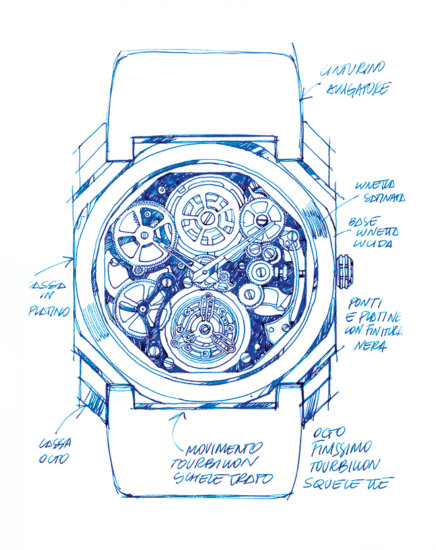

- The Bulgari Octo Tourbillon Sapphire shows off its form with a sapphire case middle

In the early days of wristwatches (pocket watches were almost universally round and so are contemporary executions, Tom Ford’s attempt to transform the Apple Watch notwithstanding), firms experimented with wildly differing shapes, only a few of which remain well known today. In the era of properly water resistant watches though, most wristwatches are round and that is just because it is much simpler to achieve ISO water resistance standards when the case of the watch is round. Once again, function keeps interfering with the notion of the form watch

The reason for this water resistance bit could very well fill another article but, to cover it briefly and intuitively, just think of how easily a rubber gasket would work with a round watch as opposed to a rectangular one. It is for this reason that even brands with a yen for specific shapes (or even just one shape in particular) opt for the round shape when necessary.

Bell & Ross makes a point about exceptional water resistance (300 metres) with the BR 03-92 Diver

Function Versus Form

An excellent, if obvious, case in point here is the Richard Mille diver watch while the equally obvious counterpoint is Bell & Ross. In fact, Bell & Ross raised the roof at BaselWorld this year by releasing a diver’s watch that maintained the brand’s signature square look. It is important to note that in this case, no pun intended, the display of time is round allowing Bell & Ross to package both form and function into the mix; obviously, the brand had to work hard to achieve exceptional water resistance in this unusual shape and that should only increase its appeal.

This example aside, function is arguably the strongest reason explaining why the watchmaking trade has doubled down on the round shape in recent years, The aforementioned standard bearers of form watches such as Jaeger-LeCoultre and Cartier are both betting big on round while Omega – once a stellar producer of shaped watches – now only features the odd bullhead and Ploprof for variation. Omega is the third largest maker of high-end mechanical timepieces in Switzerland and it has no other shape in its regular collections but round.

Richard Mille RM50-03

As for the number one spot, Rolex reintroduced the world to the rectangular Prince in 2005 in what was then considered to be yet another of the brand’s calculated surprise moves. It followed up by proposing the Cellini as a brand new tuxedo-friendly family in its collection. Unfortunately, Rolex unceremoniously ditched the rectangular Prince, with the model not even worthy of a mention on its website. If you have never heard of the Rolex Prince, it is as if it never existed…

What is particularly unfortunate here is that this is Rolex, a brand unafraid to go its own way. Perhaps no other major brand would take a chance on something major that would require some getting used to, such as the Sky-Dweller and the Yacht-Master II. If the rectangular Prince can’t make it here then the majors are truly closed for business on the form watch side. On the other hand, there are still pristine examples of the Prince available and this quirky little dressy number may yet have its day.

Chameleons: A Case in Between

All this points to the obvious truth that few brands care enough about the form segment to flood the market with options, making what’s available all the more precious. This is what Officine Panerai so smartly trades on, even resolving professional tool watch issues without compromising on the shape of the watches. Brands such as this are few and far between, and bring this story to a special class of offerings.

Audemars Piguet leads the way in disguising round watches as form watches… or is it vice versa?

Another great chameleon in this arena is Audemars Piguet, the maker of the highly idiosyncratic Royal Oak and Royal Oak Offshore watches. The shape here feels distinctive yet it maintains a sort of amorphous state, being perhaps close enough to being round that the unsuspecting eye accepts it as such. Of course, it might also be a round watch masquerading as an octagonal one. Indeed, case, bezel and crystal all come together in masterful fashion to surprise both eye and hand. In short, it is a rather beautiful ambiguity that Audemars Piguet shares here with Panerai.

Other brands too have their place here, including one collection from Patek Philippe with a shared progenitor as the Royal Oak – the Nautilus, and by extension the Aquanaut. Speaking of the great Gerald Genta, it would be remiss to ignore the current Bulgari Octo collection. Bulgari’s determination to convince the world of the virtues of its Octo shape is remarkable, making this brand one of the leading lights of the form watch segment.

Engine of Demand

Taken together, the brands that champion form watches because that is what they must do to survive and, further to that, thrive, perform an invaluable service to watchmaking as a whole – and to collectors by extension. They serve to drive the engine of demand, which is a far more difficult beast to understand than supply.

To put it another way, if while pushing their own goals and growth targets, these corporations also happen to create a little demand for gems of the past such as the A. Lange & Sohne Cabaret or the Rolex Prince, so much the better for collectors, especially those who are already moving in this direction. For those on the sidelines, the success of a particular model can lead to the brand reviving the model in its current collection or increasing its offering, thus building even more cachet and demand. There is actually a proper example of this, which brings us back to Audemars Piguet and Cartier.

The original release of the so-called Series A of the Royal Oak numbered only 1,000 watches yet the ensuing popularity of the model translated to innumerable iterations over the years. This collection – and the Royal Oak Offshore – probably contributes the lion’s share of the brand’s reported figure of 40,000 plus watches sold annually. Finishing our tale at Cartier, where we started, the success of the Tank watch might arguably be correlated to the success of Cartier as a force in high-end watchmaking. While the Royal Oak has just the Royal Oak Offshore as an offshoot, the Tank has quite a number of descendants. The popularity of the Tank with collectors inspired Cartier to create extensive options here, with no less than six different families of Tank watches available, with multiple references in each family. Not bad at all for a watch that started with just six models for sale in Paris in 1919.

Greubel Forsey Double Tourbillon 30 Degree Asymmetrical

Minor Leagues: Where Independent Watchmakers Stand on Shaped Watches

Where the big brands have circled the wagons, so to speak, it is quite a different story at smaller outfits such as Azimuth, Bell & Ross, MB&F, SevenFriday, Urwerk and others. Certainly some, especially classical names such as Philippe Dufour and Laurent Ferrier, trade on a certain inner beauty but even here, some are not afraid to bust out of the circle. This is most obvious in the watches of Greubel Forsey, where the cases literally bulge in odd ways when the function calls for it. Obviously, when one makes very small numbers of watches it is possible to take certain risks. Here’s how Max Busser of MB&F puts it:

“It’s a question of horological integrity; I’ve said from the beginning that MB&F is not going to put round movements in funky shaped cases because we’re not designers. We’re mechanical artists. This is what separates marketers from creators; If you want to please the market you probably won’t take creative risks. The bigger the company, the more you will be inclined to please the market.”

Busser’s point here extends to watches at many different prices points, as evidenced by Kickstarter notables such as Momentum Labs, Helgray and Xeric. Obviously, Kickstarter projects are defined by the marketplace so the vast majority of projects there are round watches but there are significant alternatives, which one can discover by looking at the offering from those three names.

Form Watch Movements

Proportionally, it is rewarding when watchmakers equip a rectangular watch with a movement with exactly the right shape. In first half of the 20th century, it was quite normal to expect form watches to come with movements in the corresponding shape. The idea was to have the mechanical movement function as a sort of kinetic sculpture, one where function followed form. Today, form movements are the exception rather than the rule, even within the increasingly limited area of form watches. Given that form watches as a whole are like an endangered horological species, this story concerns itself with the shape of the watch as a whole rather than the shape of the movement.

The Tank Louis Cartier and Jaeger-LeCoultre calibre 944 are both examples of kinetic sculptures

Nevertheless, an entire class of collectors follows this segment and connoisseurs of mechanical watches are always pleased when watchmakers make an effort to match the shape of the movement with the shape of the watch so in this section we will look at the history of such efforts and suggest why they have fallen out of favor, although the simple answer as to why your cushion-shaped watch comes with a round movement is not hard to fathom: it makes sense from a cost and reliability perspective.

With apologies to Louis Cartier and to play devil’s advocate, what value does it really speak to that function should follow form? It is by no means a recent development that we consider function more important than form. To reference the main part of this story, this speaks to why the Apple Watch is rectangular.

Jobs’ design ideology finds its spiritual cousin in the watchmaking philosophy of Jaeger-LeCoultre, at least when it comes to the Reverso. Other than the Squadra, the Art Deco icon has always been equipped with a form movement and its case shape was dictated by function. The Reverso has the shape that it does to facilitate its defining reversible function. Function though is where form movements run into trouble, for one obvious reason: automatic winding, or rather the lack thereof.

The newly launched Tiffany Square Watch comes with its bonafide form, square shaped movement. A rarity even amongst specialist watchmakers.

Since at least the 1960s, the watch buying public has sought out automatic models. Once again, you can look to Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Reverso models over the years to see how this played. For the most part, the Reverso has been equipped with manual-winding calibers, all form ones of course. For self-winding models, in the Reverso Squadra and elsewhere, the Grand Maison uses round movements. Cartier sidestepped the issue though because Edmond Jaeger designed and equipped the early Cartier form watches with round LeCoultre movements.

Words by Ashok Soman.