How often do you think about a leap year? The seemingly innocuous phenomenon that happens once every four years, adding a single day to February. For most of the world’s population it is probably just “oh, there is a February 29th this year” as they see the date on the screen of a smartphone, smartwatch or Google calendar. But, for us watch enthusiasts, on the other hand, February 29th is the day when we finally get to see the perpetual calendar complication go to work. The day when your mechanically driven timepiece can intuitively understand that in 2024, February doesn’t end on the 28th and therefore can automatically compensate for the extra day, and subsequently the arrival of March.

Put to a non-watch person, it may seem that all the research and development and investment from the brand side, along with the hefty asking price of a perpetual calendar, to see it in action once every 1,460 days is probably not justified. However, this is the reason you buy a perpetual calendar. Not an annual calendar or a complete calendar, which is comparatively much cheaper. You buy a perpetual calendar so you can set it once, and if continuously powered, will keep the date until 2100 whereby many of us reading this would no longer be alive.

In honour of the year that will see the Perpetual Calendar complication put to good use, for our Spring 2024 issue, we take a closer look at this complication from Blancpain. More specifically the Villeret Quantième Perpétuel Ref. 6656, a model that represents the confluence between the trifecta of complexity, functionality and design. This model from the manufacture is not new per se but for 2024 it has, for the first time, been given a deep green dial inspired by the fir forests of the Vallée de Joux and paired with an elegant red gold case, giving us the perfect opportunity to revisit the perpetual calendar complication, a complicated that many collectors would probably have on their grail list.

THE DIFFERENCE A DAY MAKES

To understand what makes a perpetual calendar so special, one must first go back to the basics of the date function. At its most basic level, the date mechanism simply follows the advance of the hour hand. For every 24 hours that pass, the date wheel is advanced one day forward. If all months had 31 days this complication wouldn’t have a problem because mechanics thrive on repetition (I recommend playing the video game Opus Magnum to better understand what I mean). However, as we know, some months have 30 days while others have 31. If this was the only variable in a calendar, then, still a perpetual calendar wouldn’t be too difficult to make as the mechanism only has to compensate for two variable factors. Adding on yet another layer of complexity is the fact that February has 28 days which makes this month out of the 12 yet another anomaly which has to be mechanically adjusted.

For each layer of ‘rule’ added to a calendar the mechanics inside have to increase exponentially in terms of complexity to comply. For example, the traditional date complication is simple to manufacture because it follows one rule, and the human (wearer) will manually compensate for the discrepancies between the different days of the month. This means that the date wheel will just automatically advance to 31 every month and five times a year this must be manually corrected.

The next layer of complexity is a movement that can discern between the months that have 30 and 31 days and automatically advance the date as such. This is the function of an annual calendar complication. To achieve this, engineers devised a special cam that takes into consideration the pattern of days in the month within a 1-year cycle. But, as the name alludes, the Annual calendar still requires one manual adjustment to the date every year which is in February, regardless of whether it is a leap year. Interestingly enough, even though the perpetual calendar was invented by Thomas Mudge around the 1760s it was only in 1996 that the simpler annual calendar was invented.

For a perpetual calendar to work, the mechanism within the movement has to be capable of not just ‘understanding’ the patterns of 30 and 31 days within a year, it also has to ‘remember’ that February has only 28 days. And the most important of which, is it has to keep track that every four years, during a leap year, there is an extra day on February 29th. Explaining the mechanism to achieve this would probably take more pages than we have for this article so for the sake of brevity, the ‘memory’ of a perpetual calendar can be boiled down to a cleverly designed cam that records the length of months in a four-year cycle. For this Ref. 6656 specifically, the cam is based on an 8-year cycle recording two consecutive leap years, which can clearly be observed on the subdial at 12 o’clock. On paper, it may seem simple enough to add one day to February every four years, but in reality, the Perpetual calendar is even more complicated than the fan-favourite tourbillon and is probably closer in number of parts to a minute repeater.

Within this new version of the Villeret Quantième Perpétuel Ref. 6656, beats the calibre 5954 automatic movement with its integrated perpetual calendar complication. It is capable of offering a power reserve of 72 hours when fully wound and offers the same anti-magnetic properties thanks to its silicon hairspring.

Even though the word perpetual suggests that the watch need not ever be adjusted, Blancpain’s perpetual calendar, and for that matter almost all perpetual calendar complications are not perfect because they still must be manually adjusted in 2100. If you take the rule that a leap year happens every year divisible by four, then technically 2100 should be a leap year. But it’s not. This is because the exact time that Earth makes a full rotation around the sun is not exactly 365.25 days but rather 365.2422 days. By this logic, if we continue to apply the leap year rule, after a couple of hundred cycles, our seasons will start to get out of sync. Therefore, when the Gregorian calendar (the one we use today) was invented it stated that century years would have to be divisible by 400 for it to be a leap year. Thus 2100, 2200 and so on, will not be leap years to compensate.

BETTER SAFE THAN SORRY

On the subject of manual corrections, the perpetual calendar complication can be notorious when it comes to its adjustments. In perpetual calendars of the past, it has been said that manipulating and adjusting the watch at certain times could easily damage the watch earning it a round trip home to Switzerland and along with it, a large bill for the repairs. And this forbidden period was between the few hours before midnight and the few hours that followed. During this time, the calendar indications are changing, and any manual correction applied could easily damage the delicate gears.

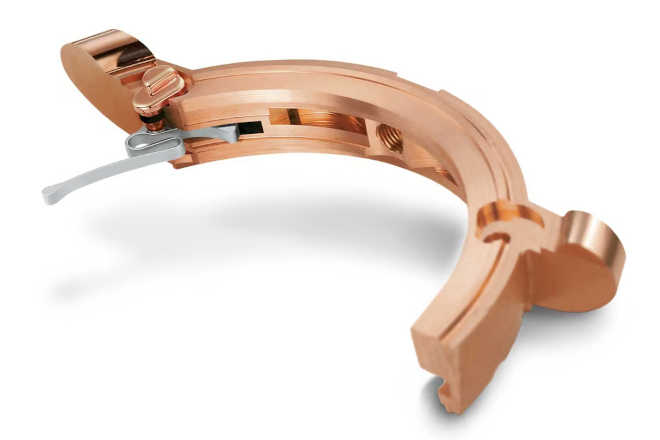

With the Villeret Quantième Perpétuel Ref. 6656 from Blancpain, this is no longer an issue as the watch designers at the manufacture have managed to eliminate this risk entirely. When the user tries to make the adjustment while changes are happening, a clutch disengages the system to prevent any damages from occurring. But the ability to do this doesn’t come without its cost, and according to Blancpain, they needed 40 per cent more components compared to a traditional complication to achieve this. Of course, all of this is hidden beneath the dial so all the wearer sees, is a clean and elegant design on its top side.

Another testament to the usability of Blancpain’s perpetual calendar movements is the fact that since 2005 they have introduced a patented system of manual adjustment – under-lug correctors. Traditionally these manual adjustment mechanisms have always been built into the sides of the cases. In fact, most other perpetual calendars still use these correctors, which appear as small dimples on the case of the watches. The clever use of under-lug correctors by Blancpain enhances the watch in two ways.

The first of which is purely functional where instead of needing a tool to depress the dimples on the case, the lever on the underside of the lugs can be manipulated using one’s fingernails. Secondly, the discarding of these dimples can now allow the watch case to have an entirely smooth surface, adding heaps to the elegance of the watch. This is especially prominent in the case of the Reference 6656 where the beautifully minimalistic dial is complemented by the blemish-free red gold polished case.

MOON FACE INDICATOR

Okay, before you grab your pitchforks protesting this sub-heading, it is indeed quite a literal reference to the little face present on the moonphase indicator on the dial. The moonphase has always been a significant part of Blancpain’s history; One could even say that it is the perfect representation of Blancpain’s ethos as a watch company.

As the story goes, the legendary Jean-Claude Biver said when he bought Blancpain in 1982: “There has never been a quartz Blancpain, and there never will be.” Back then, even the Swiss watch brands were starting to dabble with quartz technology during the era of the quartz crisis. But Blancpain took an opposite stance, instead, doubling down its efforts to cement the mechanical watch’s place in contemporary times by demonstrating how quartz could never replicate the complexity, craftsmanship and history of traditional watchmaking. One of the first complications they decided to make in its modern era was a moon phase indicator in 1983.

Looking at the moon phase indicator on the new Villeret Quantième Perpétuel Ref. 6656, I feel like the face on this moon is portraying something akin to an all-knowing smirk. Perhaps it knows that Blancpain’s choice to make a statement with this complication basically predicted the role of the mechanical watch for contemporary times, not just for Blancpain, but arguably for the entire luxury watch industry that exists today.

The design of the dial is the same Ref. 6656 that was first launched in 2018 which also served as a replacement for the Ref. 6057 which offered a similar design, day, date, month and leap year indicators in three subdials, but in a smaller 38mm case. The new Ref 6656 on the other hand is housed in a 40mm red gold case complete with the collection’s signature double-stepped case. Last but certainly not least, the new look is also defined by the mesmerising, deep green of the dial. The colour along with its sunburst pattern was inspired by the fir forests of the Vallée de Joux that surround the Grandes Complications workshop where the watch is meticulously crafted by its master watchmakers.